Days of Collection, Days of Despair

April 25, 202437 minutes

A tale of evolution from ChimeraPy to SyncFlow

Note 1: This document was reviewed and corrected for spelling and grammar with the assistance of AI-based tools.

Note 2: SyncFlow was initially named as LiveKitMMLA.

Note 3: The top level domain used for the IACT study was changed from livekit-mmla.org to syncflow.org for the sake of clarity in the narrative of the blog post.

Contents

- Introduction

- MMLA Collection and Processing

- The V1: ChimeraPy

- GEM-STEP Fall 2023 (GSDCP)

- The Shift to LiveKit: A Rationale

- LiveKit Integration: SyncFlow

- IACT Study: Spring 2024

- Practical Outcomes, Experiences and Lessons Learned

- The Road Ahead

- Call To Action

- Special Mention: Eduardo

- Thanks NSF

Introduction

In my relative short stint at Open Ended Learning Environments lab(OELE) at Vanderbilt University, I quickly found that learning science research and the core concepts are way above my pay grade. However, as with any research domain, there are various aspects in which richer computer science theory / tooling can not only streamline the processes in a domain, but also provide richer context and evidences to support / disregard what are the core theories in that domain. This was my initial days of foraying into multimedia streaming and Multi-modal collection in general. This blog post is a reflection of challenges faced, good and not so good experiences, design decisions and the road ahead for this direction and what I learned from almost an year’s worth of work in this domain.

But even before that, my current role came into existence followed by an unfortunate end to a previous DARPA project and thanks to the NSF Engage AI institute for investing in a Multi-modal learning analytics strand and delegating OELE as its leader, for which I was hired to develop and test platform and infrastructure for collecting and analysis of Multi-modal data for education, specifically, for the classroom studies conducted with the learning environments like C2STEM, Betty’s Brain, GEM-STEP and EcoJourneys etc… by the researchers in the institute. The eventual goal of this project is to come up with a unified software architecture to collect and process multi-modal data from these learning environments at scale, with a goal to (a.) Automate some of the tedious processes within the domain and (b.) Generate meaningful artifacts as feedback to learning environments and researchers for tangible research outcomes as well as enhanced teacher/students’ experiences for teaching/learning.

MMLA Collection and Processing

Multi-modal learning analytics uses data streams of different modalities to analyze and provide feedback to researchers/educators on overall performance of students performing a learning activity, typically using computers. Depending on the nature of the activity, analyses can range from affect detection, log analysis, audio transcription etc… among others. Some of these analytics methods are available in realtime.

MM collection in a typical classroom research project(usually ranging from few days to months), for each session, students are assigned a particular learning experience, these learning experiences are usually gamified(some are even games) that the students play. For each session, depending on the kinds of analysis needed, researchers usually collect application logs, students’ audio and video, overall classroom video/audio, teacher/researchers’ interviews, data from a wide array of sensors like eye trackers, heartbeat sensors, positional data etc… Well, That’s a lot right? Complicating things, the systems generating this volume of data are isolated, controlled by different actors and are built using a wide array of tools/technologies and usually there isn’t a level of synergy between them. Additionally, for a session(running from a few minutes to an hour or two), a unified timeline is needed to do a segmented analysis, such that all the collected data can be analyzed as a whole or in segments.

Here, I have itemized a list of challenges on collecting and analyzing multi modal data for learning analytics. Some of these are purely technical in nature, while others are philosophical concerns affecting the technical implementations at a fundamental level.

Integration: Combining data from diverse sources and formats is probably the most tedious aspect of collecting multi-modal data. Firstly, there are a wide range of devices and sensors (multi-modal) used in MMLA research. Anecdotally, here at OELE, we have worked with different sensors including but not limited to audio interfaces, Tobii glasses, web cameras, wireless microphones, stereo cameras, Kinect, etc. The first integration challenge is to write appropriate streaming and control software to get data from the device(s) because of the diversity in devices and their control SDK encompassing various programming languages, frameworks, and software patterns. The second integration challenge arises in getting application logs/other data from a wide array of learning environments (mentioned above). Not only are these learning environments themselves built using a plethora of technologies, but they also employ various strategies for user management and differ in their business logic, such that a unified interface to getting application logs is challenging. A silver lining in this context, however, is that most of these applications are served from the browser, so, a single JavaScript SDK can provide a solution, especially if we intended to use client-side JavaScript. The integration of multi-modal data for classroom research is further complicated by its hierarchical structure, which may include both group and individual data layers, and these boundaries are not so well defined.

Synchronization: Aligning data streams to a unified timeline poses another significant challenge in multimodal data collection, especially when there are multiple sensors streaming data at different bit rates and with actors (both human and sensors) having different times of entry and exit. Any MMLA data collection ecosystem should be deemed useless if it doesn’t guarantee synchronization of the modalities such that all the collected data can be analyzed as a whole or in segments.

Privacy: Managing sensitive information, especially with audio and video recordings, poses another set of challenges in multimodal data collection. To an external observer, a multimodal data collection system for MMLA can appear no different from an advanced surveillance system, bringing with it all the associated privacy concerns. There should be sufficient privacy guardrails in place such that participants are anonymized from the outset, and we should follow proper guidelines on how identifiable data is collected and shared, adhering to IRB and compliance policies. This domain cannot and should not operate like a leeching corporation, where a 100-page privacy policy document allows one to get away with daylight robbery. While this is not a direct technical concern or challenge, addressing privacy concerns can and should guide the architecture of an MMLA data collection system.

Scalability: Handling large volumes of data generated from multiple modalities and users poses a technical challenge, similar to other software engineering domains, when issues of scale must be addressed. Scaling becomes particularly challenging with video and audio data, as they tend to consume substantial system bandwidth and require significant disk storage.

Data Quality: Maintaining high standards of accuracy and reliability in data poses significant challenges, including addressing device failures and bugs in various closed, lightly coupled systems. Ensuring consistency across different modalities, especially when they are subject to variable environmental conditions or differing operational standards, further complicates this issue.

Resource Intensity: Managing the significant resources required for data processing and storage involves not only substantial financial costs but also technical considerations such as optimizing data throughput and storage efficiency. The complexity increases as the volume and variety of data expand, requiring more robust and scalable infrastructure solutions.

Ethical Concerns: Addressing ethical issues around surveillance and consent in educational settings is critical. It involves navigating privacy laws, securing informed consent from participants, and maintaining transparency about data use. These concerns are especially acute given the intrusive nature of some data collection methods, such as continuous video and audio monitoring, which can raise significant privacy and ethical red flags.

Overall, these challenges need to be addressed when developing systems for multi modal data collection for learning analytics. To that end, our goal through out the endeavor was to develop and build integration channels for the exact system, which we will aptly call the Multi Modal Learning Analytics Pipeline (MMLA Pipeline).

The V1: ChimeraPy

ChimeraPy is a distributed computing framework for multimodal data dollection, processing, and feedback. It’s a real-time streaming tool that leverages from a distributed cluster to empower AI-driven applications.

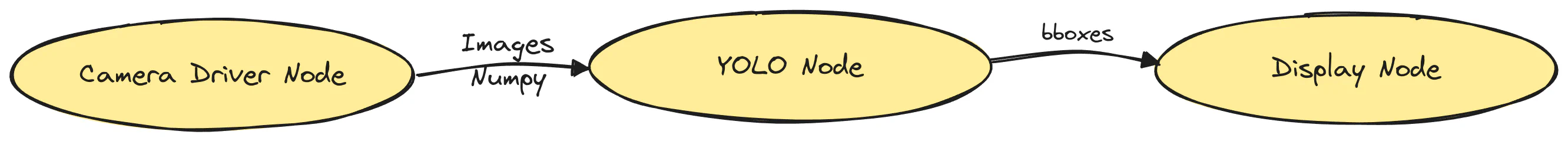

When I joined OELE, Eduardo had already started working on a multi-modal data collection system, which he had named ChimeraPy. The name Chimera[Py] comes from Greek mythology, describing a creature with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a serpent, which he thought would be a fitting name for a system that integrates data from diverse sources. The first iteration of ChimeraPy included a client-server architecture with WebSockets to stream data, which Eduardo had finished refactoring to use ZeroMQ sockets by the time I had joined. At its core, ChimeraPy used an HTTP Server as a “Manager”, which could be discovered by clients on the network called “Workers”. The workers would register themselves as available to take on a streaming task. The streaming architecture used Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), and the node in a graph was a basic unit of computation that would either generate or consume data. These nodes were implemented as Python processes that would eventually be pickled and delivered to workers based on a mapping provided, a process known as Commit-Graph in ChimeraPy lingo. For example, if we wanted to create a face detection pipeline using, say, YOLO with a web camera, we would first create the following graph:

A simple YOLO Face Detection Pipeline, represented as a DAG in ChimeraPy

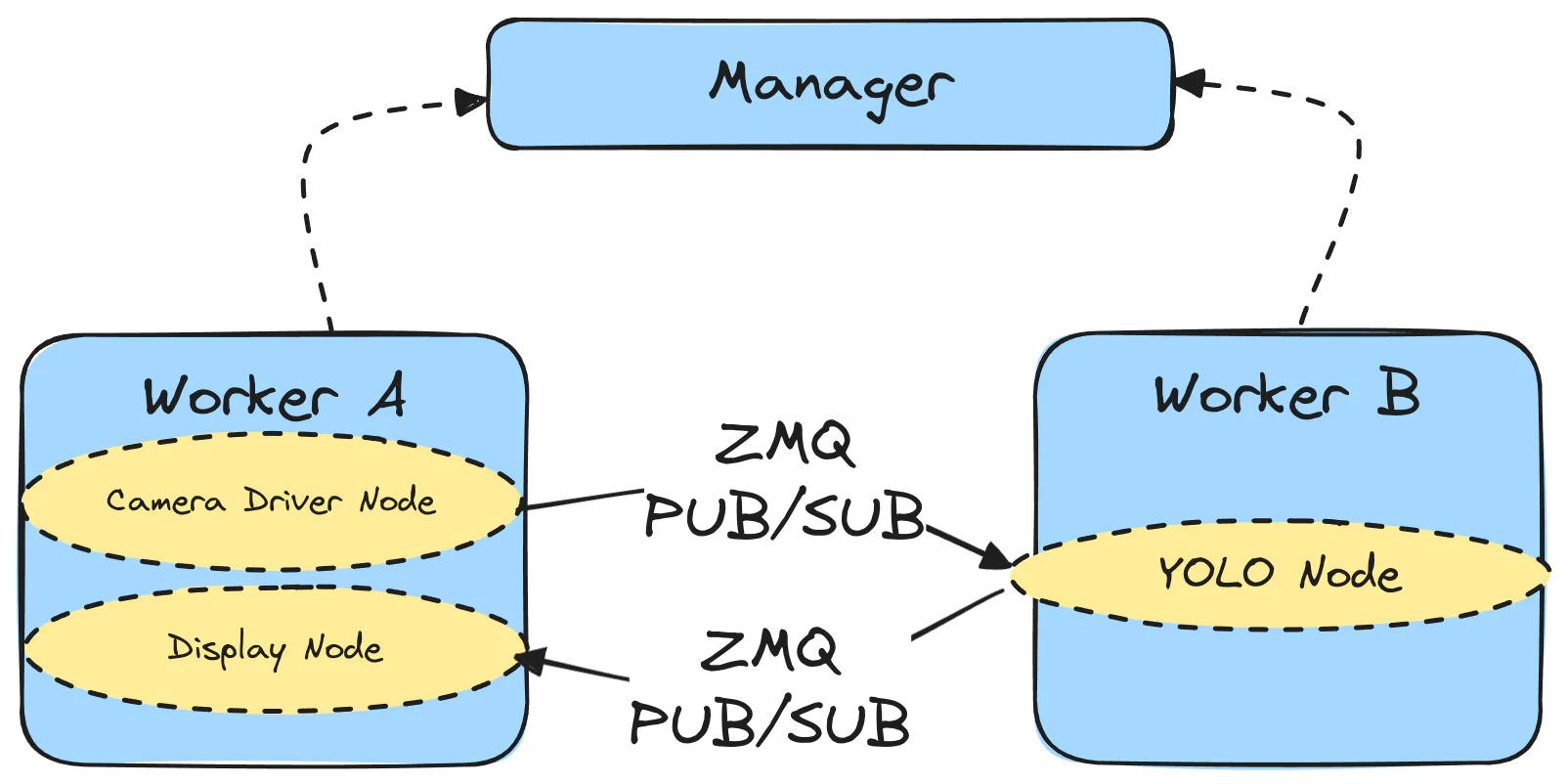

In this case, depending on the workers available for a particular cluster instance, we would create a mapping (many-to-one) between nodes and workers. For instance, if we had a GPU machine to run YOLO and another machine to handle the camera and display, we would register two workers with the manager. Then, the action to commit the graph would involve distributing nodes to the workers according to the provided mapping, as shown in the figure below:

A visual depiction of the commit graph action in ChimeraPy

In the context of this data flow architecture, each Node must implement three critical functions: setup, step, and teardown. During the setup phase, the node initializes all necessary resources, such as capturing data inputs and loading models (e.g., YOLO for image recognition tasks). The step function is executed repetitively to process data in a streaming manner. Finally, the teardown function is called to release resources when the node’s operation is completed. Importantly, the nature of each node’s communication role in the graph is determined by its edges: nodes on the outbound edges act as publishers, disseminating data to subsequent nodes, while nodes on the inbound edges serve as subscribers, receiving data from preceding nodes in the graph. Further details of the actual streaming architecture and the whole ecosystem can be found in our paper, linked here.

So far, we have only discussed the streaming aspects of ChimeraPy; however, as previously noted, streaming and processing multimodal data is only one aspect, and storage is another. In ChimeraPy, rather than using a centralized entity to record individual modalities, the data is recorded by individual workers executing the nodes. After the streaming operation is over (the manager is directed to stop), the recorded data is packaged and sent to the Manager via network file transfer. This approach strikes the right balance between not having to use too many sockets to record data and achieving centralized collection. Additionally, the Node in ChimeraPy provides built-in support to record video, audio, text, JSON, etc., via parametric functions that users can utilize in its step function to save the data generated by the Node.

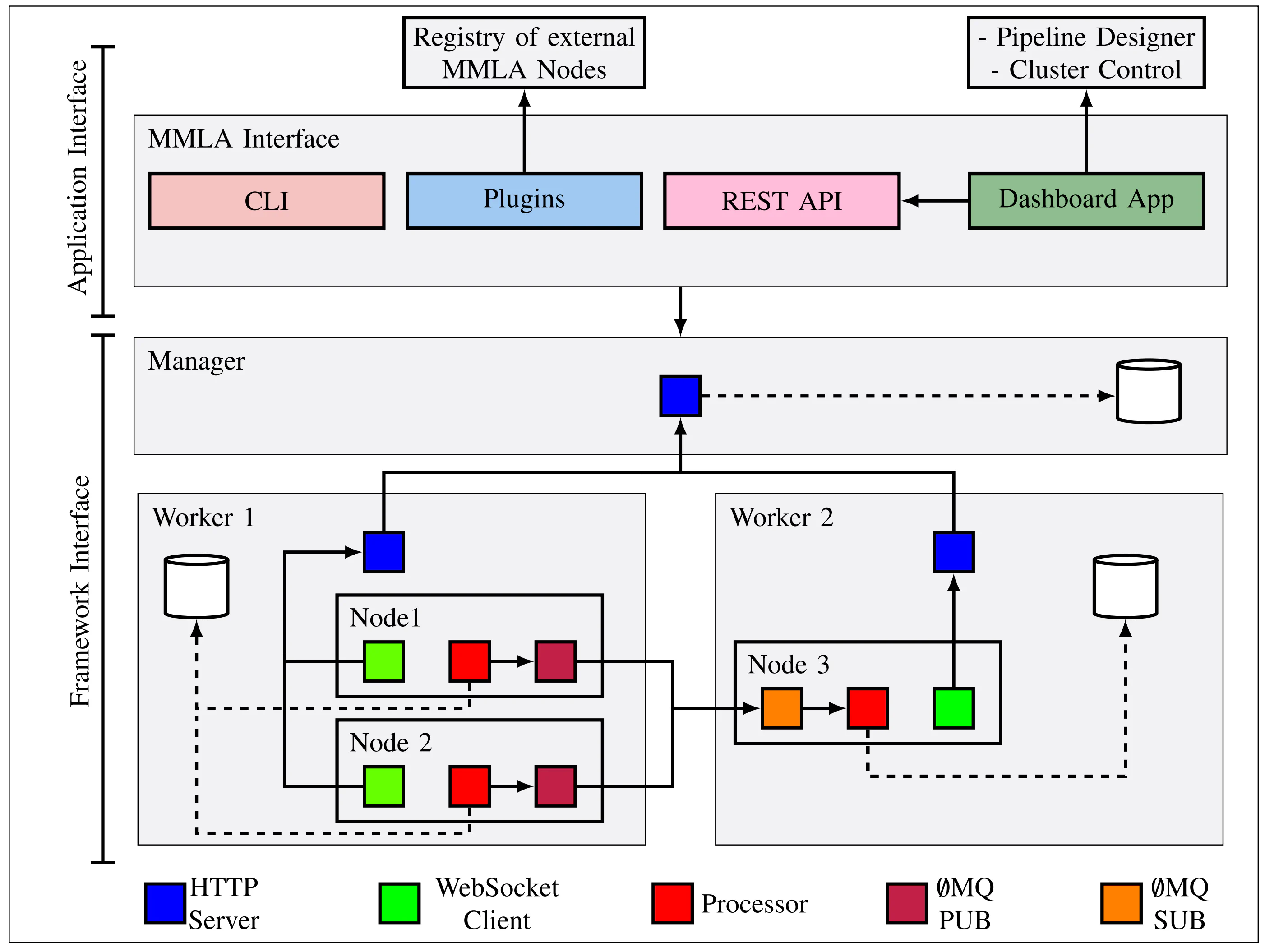

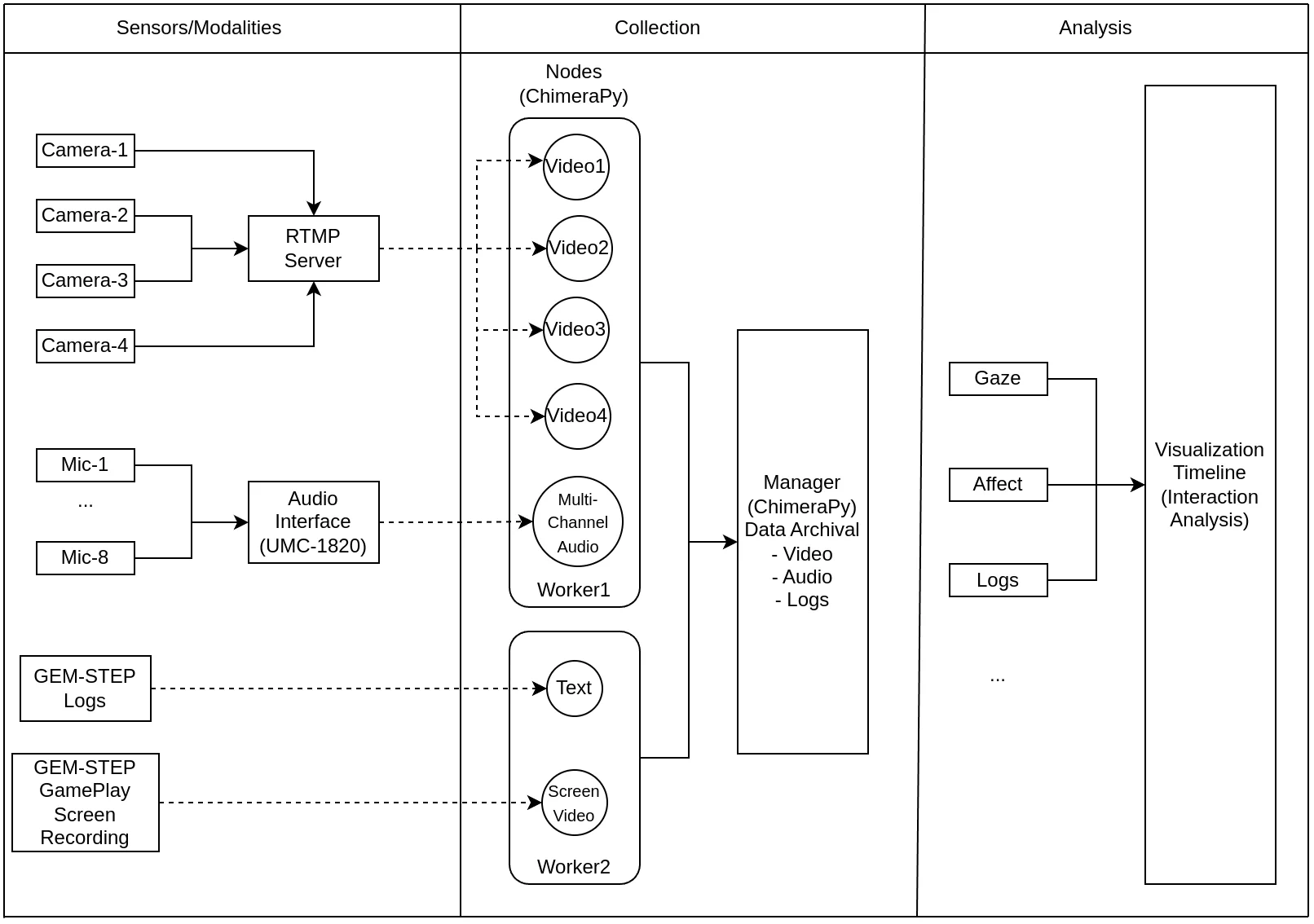

The bare bones of the streaming system were ready, although had to handle numerous bug fixes and pattern changes. Eduardo was already using the system to collect data for his Reading Project, with some level of success. However, there were various shortcomings and additional features we wanted to cover. First of all, we realized that DAG construction via Python scripts was untenable due to the portability issues of those scripts. Secondly, we needed a configurable way to reuse the nodes that we wrote for a project and to create an ecosystem of reusable nodes. Thirdly, since this system was intended to be used by researchers, we wanted to employ concepts from meta-programming so that nodes and the DAG could be created and deployed from a web dashboard. This led to the development of ChimeraPy/Orchestrator and the eventual refactoring of the networking engine from ChimeraPy to ChimeraPy/Engine. The ChimeraPyOrchestrator would eventually provide reusable nodes and an orchestration scheme/dashboard application for ChimeraPy with JSON configuration. We also created ChimeraPy/Pipelines, a repository of shareable ChimeraPy pipelines. Leveraging the Orchestrator and Engine constructs, we achieved an application interface for the ChimeraPy framework, which we used for writing various MMLA collection and analytics applications. There were quite a few feature backlogs as well as bug fixes needed, but we had achieved a functional CLI and system for using reusable software to stream, process, and collect multi-modal data, leading to the following system diagram.

Detailed System Diagram for ChimeraPy: Broken into 2 sections: (1) Framework Interface, composed of the Manager, Worker, and Node, performs the cluster setup, configuration, execution, and data aggregation. (2) Application Interface, made up of a CLI, plugin registry, REST API, and a Web app, provides the tooling and scaffolding for pipeline design, deployment, and orchestration.

Now it was time to put the system to the test. The initial trial occurred during the GEM-STEP retreat in the summer of 2023, where we collected audio and video data from six web cameras and microphones as graduate students engaged with the game. Subsequently, we used ChimeraPy to develop several demos for the EngageAI site visit and additional pipelines for benchmarking as well. However, the first significant real-world application emerged when we had to develop a data collection pipeline for a classroom study conducted in October and November 2023 at an elementary school in southern United States.

GEMSTEP Fall 2023 (GSDCP)

In the beginning of Fall 2023, we were tasked with developing a data collection pipeline for the GEM-STEP study, which was to be conducted at an elementary school in southern United States. The study was a collaboration between Noel Enyedy’s group from the Peabody campus at Vanderbilt and OELE. Several PhD students from his group and from our lab, including Joyce, Eduardo, and myself, were responsible for the research and technical aspects of the study.

In the GEM-STEP project, students embody characters in a game and learn about various scientific processes and concepts. The game utilizes a Pozyx system to track students in the play area, and their positions are mapped to a screen. One module, for example, might focus on Photosynthesis, where students embody molecules and move around the play area to collect sunlight and water. The game is designed for group play, and students are expected to collaborate to achieve the learning objectives. During game play, the system generates game logs that would later be used in analysis. Usually, students move around the play area, looking at a big screen that has projections from the game.

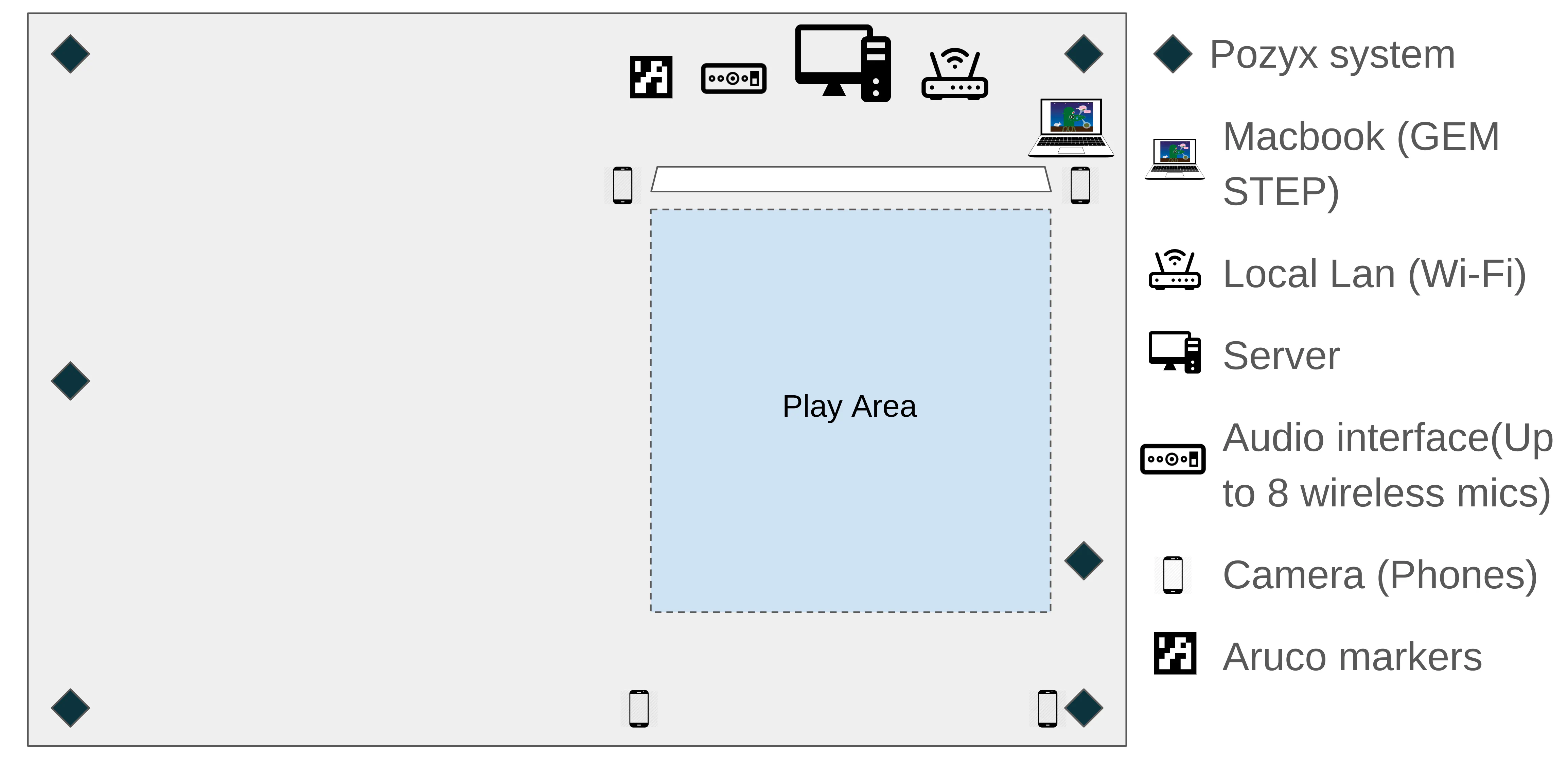

The data collection requirements for our study at the school included collecting (a) students’ and teachers’ audio, (b) gameplay video from multiple angles, (c) game logs, and (d) gameplay screen captures. Given the limitations of space for device placement in the classroom and the lack of internet access, we needed to adapt our approach to supplement the traditional data collection methods used by Noel’s group without replacing them.

Joyce discovered the UMC1820 audio interface from Behringer, which could collect audio from eight wireless microphones simultaneously. This capability was sufficient to capture audio from all students and the teacher. Considering the space and hardware constraints in the classroom, we ruled out the use of wired cameras for video streaming. Instead, we considered using smartphones due to their portability and minimal space requirements. After researching various apps capable of streaming video from phones, such as DroidCam, EpocCam, IPWebCam, IVCam, IRIUN, and Larix Broadcaster, we invested time in selecting a suitable budget phone and tripod mounts, eventually choosing the Pixel 7a.

For accurate vision-based position estimation and camera pose estimation in the gameplay area, we opted to use Aruco Markers. This combination of technologies allowed us to effectively collect comprehensive data while accommodating the physical and technical constraints of the classroom environment.

The data collection setup for GEMSTEP study of fall 2023. 4 phones, audio interface and a macbook, together with the ChimeraPy server were used to collect data from the classroom

The data collected was stored on the server and replicated across two SSD disks. Initially, everything worked great; however, upon reviewing the video footage and based on Ashwin’s suggestion, we realized we needed to use the wide-angle cameras in the Pixel 7a, which none of the aforementioned apps supported, barring the Larix broadcaster. However, the setup to make that work was quite complicated. Eventually, we found CameraFi Live, which enabled us to work with the wide-angle lens in the phone, but required us to host a separate RTMP server on-premises. I found a helpful blog post on how to host an RTMP server using NGINX. However, there was a significant delay in the feed and the eventual video that was saved, which Joyce had to do a lot of post-processing on to synchronize everything, a compromise we accepted, leading to the following architecture:

The eventual architecture of the GEM-STEP Classroom Study Data Collection Pipeline

Overall, during the 45-day-long study (October-November 2023), ChimeraPy and the data collection pipeline we developed managed to collect close to 1 terabyte of data, which our peers eventually used to write an AIED paper. We continue to use this data for vision-based automated interaction analysis (Visualization Timeline). While the study was a relative success, we all recognized that there was room for improvement. Nevertheless, considering the time and space constraints, we were satisfied with the overall endeavor. The github repository is linked here.

At this point, I was relentlessly traveling to the school, fixing code, and transporting hardware back and forth from ISIS to the school for hardware and software fixes. After a month or so of helping out Joyce in the classroom study, I felt quite burnt out, having not taken a proper vacation in 2 years. I discussed with Prof. Biswas, my supervisor, the possibility of taking a 45-day-long vacation. With his blessing, I booked my flights, packed my bags, and flew to Nepal in late November 2023.

The Shift to Livekit: A Rationale

At this point, we had multiple reasons for being unhappy with the state of things in ChimeraPy. Firstly, while we were happy with developing things and writing Python Nodes (1, 2, 3), we still hadn’t thought out and planned a proper architecture to get data from the browsers, which would be crucial for the learning environments we needed to integrate. Using ZeroMQ in browsers wasn’t as straightforward as we had thought. Secondly, and perhaps more significantly, we found that most of our time was spent developing and testing the underlying networking infrastructure, and we were nowhere near feature-complete to begin integrating and advertising the multimodal pipeline with ChimeraPy in some of the external and internal learning environments. At OELE, we have to adhere to tighter deadlines, and we were already behind schedule. Additionally, the goal of this research software development endeavor was to develop multimodal data collection/analysis applications rather than developing a distributed streaming framework, which, to be honest, felt like reinventing the wheel a lot of the time. Thirdly, while ChimeraPy worked great for one-off classroom studies with a few streams, the real challenge for us was to scale it to a classroom study with hundreds of streams and deliver it from the cloud.

This was the point after the GEM-STEP study of fall 2023, and I was on vacation. This is when Eduardo and I decided to deliberate on possible steps ahead. We had a lot of discussions, and Eduardo was thinking about extending the ChimeraPy architecture, while I was looking for some open-source solutions that we could leverage.

Overall, we had come to the following takeaways from our discussions:

- We need to focus on the deliverables rather than the underlying networking infrastructure.

- WebRTC could be a viable solution for our browser integration needs.

- Local infrastructure was not scalable for our needs, and we needed to move to the cloud.

A lot of our architectural deliberations are diagrammed in the following draw.io diagram. Eduardo even wrote up an entire design document for ChimeraJS, which was a proposed extension to ChimeraPy to support browsers. I looked into a few media servers like mediamtx, ant media server etc., to see if we could leverage those servers and repurpose them for streaming as well as writing browser adapters, but none of them seemed to fit the use case we had in mind. We also looked into PeerJS and PeerJS-Python, using which we could solve the browser integration problem. All three approaches had their pros and cons, enlisted below:

Option 1: ChimeraJS + Integrations with ChimeraPy

The pros of this was that we didn’t have to do a lot of pivoting to support this. We could leverage the existing architecture and use an aiortc adapter to support WebRTC. This would also let us have our own WebRTC-based tech stack and would fit a lot of our needs at a lower scale. The cons were that we would still have to develop and test the underlying networking infrastructure, which was a major bottleneck for us. Additionally, leveraging cloud infrastructure would be a challenge, and we would have to do a lot of work to make it work.

Option 2: Media Servers

The pros of this approach would be that we would get a ready-to-use infrastructure to support streaming multimodal data, and we would be able to support a wide array of protocols like RTMP, SRT, and WebRTC. Specifically, we looked into ANT Media Server and MediaMTX. The cons were that we would have to write a lot of computation infrastructure code to support our use case, and we would have to do a lot of work to make it work.

Option 3: PeerJS

The advantages of using PeerJS include the ability to enable peer-to-peer (P2P) communication utilizing WebRTC, with the support of a custom signaling server hosted in the cloud, which fits well within our existing Python-based infrastructure. This compatibility reduces the need for significant changes to our current system. However, PeerJS presents challenges in terms of scalability, as it is primarily designed for P2P interactions and may struggle under the load of larger, more complex deployments. Moreover, its reliance on P2P connections restricts it to scenarios that do not require centralized control or data aggregation. Additional considerations include the necessity of a robust cloud infrastructure to manage the signaling server effectively, which could increase complexity and costs.

Overall, none of these solutions we looked into really fit our use case, and then one fine morning, from a cafe in Bharatpur, Nepal, I sent out a Slack message to Eduardo about a new open-source project I had found, called LiveKit, that touted itself as an open-source, scalable, and secure WebRTC infrastructure. This seemed promising to me in the beginning, however, I have to admit that I didn’t know much about it when I sent it to Eduardo. Eduardo, to his credit, did the initial research about LiveKit and had come to the realization that this infrastructure was exactly what we needed. We were on the lookout for an infrastructure that:

- Respects the Open Source Philosophy

- Supports data collection from a wide range of devices/environments

- Doesn’t need a lot of reinventing of wheels to fit our use cases

- Easy to use with browsers as well as local IoT devices

- Has support for processing streams locally as well as in the cloud

Eventually, my vacation days were over, and I flew back to Nashville. At this point, we had decided that before pivoting to LiveKit, we should at least explore all the features in a way such that we could make an informed decision. I did a lot of reading, like this very informative blog post and the entirety of the LiveKit documentation to actually understand the capabilities we would be getting with LiveKit. With this information, I also worked on a small proof of concept to see if we could leverage LiveKit to fit our use case.

In hindsight, the MMLA collection and analysis requirements are similar to those of video/audio conferencing applications, with an added level of complexity due to the need to support different hierarchies for group and individual audio, peripheral IoT devices, and other kinds of data discussed above. The one difference is that a video conferencing application has true peer-to-peer delivery from the get-go, whether using pure P2P protocols or an SFU, while data collection in an MMLA setup requires centralized collection and processing with selective peer-to-peer delivery. However, this is beyond the point of analogy between video conferencing and MMLA collection.

First, similar to video conferencing applications, both contexts involve multiple participants (humans as well as bots).

Second, both require real-time data processing and delivery.

Third, depending on the application requirements, the software facilitating both should be scalable and delivered from the cloud.

Fourth, and probably the most similar aspect, is that both fundamentally include streaming audio, video, and data from multiple sources and processing them in real-time.

Similar to a timed video call in conferencing, a classroom study in MMLA has a start and end time, and the data collected during this period is saved (similar to recording online meetings), and can be processed both in real time and post-hoc. On the other side, synchronization and data quality are likely more important in MMLA collection than in video conferencing, as the data collected in MMLA should be mapped to a unified timeline and be of high quality to be used for analysis. This was probably the biggest selling point for LiveKit, as it supported all these features out of the box, and we could leverage it to fit our use case.

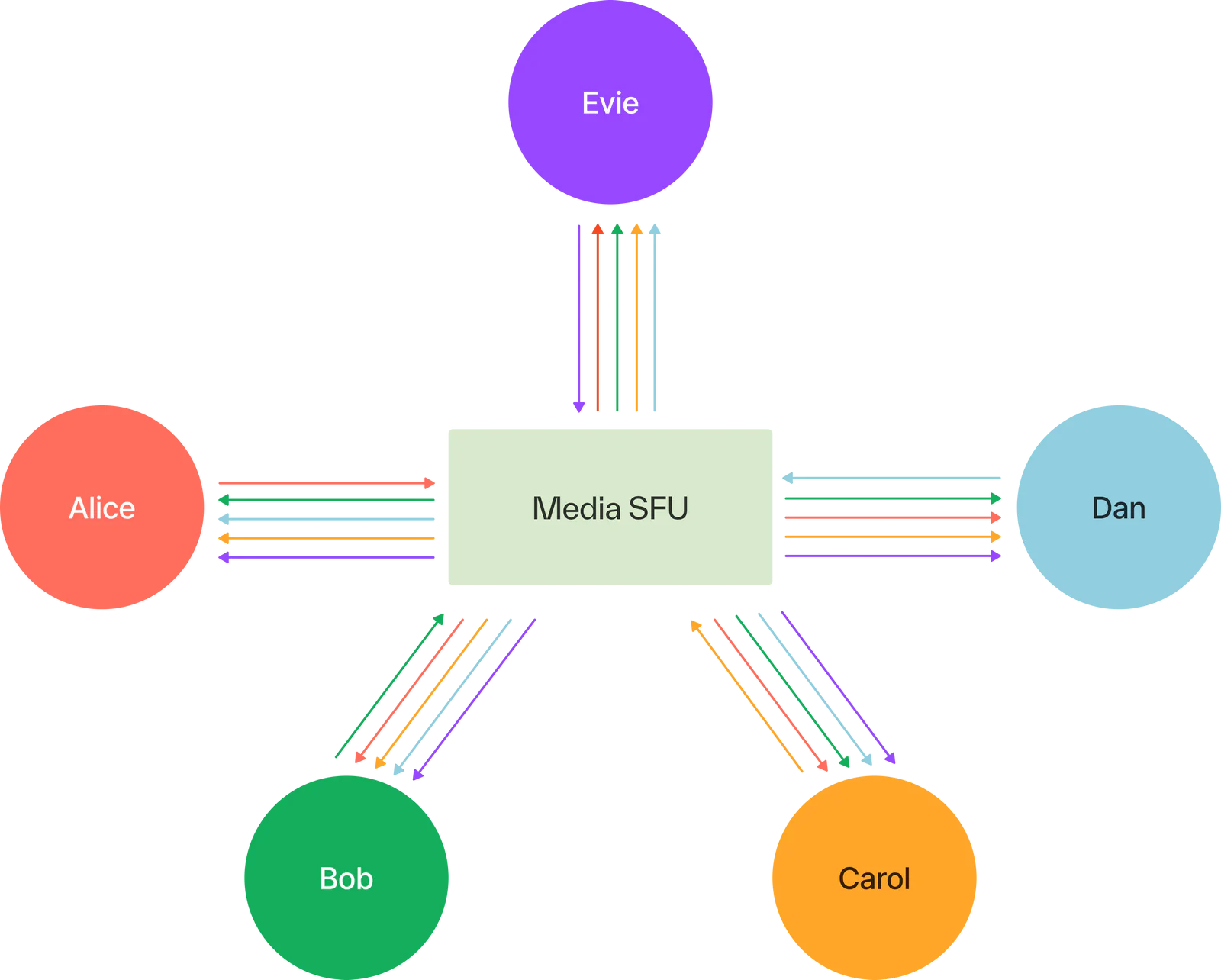

Simply put, LiveKit is an open-source project that enables the creation of scalable, real-time video and audio applications. It essentially allows developers to build an open-source tool similar to Zoom or Google Meet. At its core, the LiveKit server functions as a Selective Forwarding Unit (SFU) media server. This setup allows participants to join a LiveKit “Room” and send or receive audio to and from other peers in the room. It supports both streaming and video conferencing.

A visual representation of LiveKit’s SFU architecture

One of the standout features of the LiveKit ecosystem is that it is completely open-source, and there is comprehensive documentation available on how to deploy it. LiveKit also offers a wide range of SDKs and APIs, allowing for the development of applications in languages and frameworks such as JavaScript, Python, Rust, Unity, and more. Essentially, it provides a one-stop solution for building video and audio applications. In note of an earlier point about the diversity of systems used in MMLA research, having a lot of out-of-box support is ideal.

In our specific context, the most significant advantage was LiveKit’s out-of-the-box support for video, audio, and screen, as well as data streaming from the browser, which had been a major bottleneck in our ChimeraPy project. Additionally, LiveKit’s Egress feature allows for saving the streams to cloud storage, with synchronization achieved via seconds from the Unix epoch as timestamps for audio and video data. Furthermore, the Agents framework in LiveKit offers a streamlined solution for processing and providing feedback on participants’ streams. All of these features made it clear that pivoting to LiveKit was the right move for us, and we were ready to make the switch.

LiveKit Integration: SyncFlow

Before we dive into how we integrated LiveKit, let’s examine what a typical “LiveKit Workflow” looks like. A LiveKit server can either be self-hosted or accessed via the LiveKit Cloud for an already operational LiveKit deployment. Typically, a server has a ws(s) URL that clients need to connect to. Additionally, to send authenticated requests to the server, a set of API key-secret pairs must be generated.

The LiveKit SDKs are divided into two main categories:

- Server SDKs: These are used for backend operations such as creating rooms, generating join tokens, and managing room recordings.

- Realtime SDKs: These are used on the client side for streaming media to the room.

For successful integration, the backend should enable clients in the system to request room join tokens, complete with customizable video grants, which clients can then use to enter the LiveKit room via the Realtime SDKs. The server-side SDKs manage tasks such as creating rooms, deleting rooms, listing rooms, and starting room egress, among others. Meanwhile, the Realtime SDK includes utilities for streaming from media devices, functions for joining and leaving rooms, setting room presets, streaming data, and more. This comprehensive setup allows for robust and versatile interaction within the LiveKit ecosystem. Further details on this can be found in the LiveKit documentation.

Once we decided to make the switch, I realized that a good starter project for integrating LiveKit would be to rewrite the GEM-STEP data collection pipeline using LiveKit. At that time, we didn’t have any specific studies or deadlines pending, so I thought this would be a valuable exercise and could potentially benefit a future study scheduled for the fall of 2024. Within the LiveKit ecosystem, the NextJS and React-based integration seemed the simplest and offered the least resistance. Therefore, I started with a NextJS application that could create a LiveKit room (using the LiveKit server-sdk-js), where admin users in the application would be able to share cameras and microphones (using LiveKit React components).

For the collection aspect of the GEM-STEP Data Collection Pipeline (GSDCP), the solution involved using AWS S3 buckets for storage and recording. Initially, I utilized LiveKit Cloud for local development and testing, but I soon realized that using a locally deployed LiveKit server would be more effective and straightforward for local development. The NextJS app was initially deployed on Vercel and used a free Vercel PostgreSQL database with Prisma as the ORM.

This exercise was particularly effective as it allowed me to delve deeper into how things operate within the LiveKit ecosystem. The extensive React components library provided by LiveKit made the development experience smoother. At the time, I also explored implementations for Meet and Kitt, two example projects within LiveKit that utilized the React components library. The LiveKit GitHub repository offers excellent starter examples for nearly every SDK, which greatly facilitates newcomers to the ecosystem. Additionally, the community support provided by their Slack channel was outstanding, offering helpful responses to a wide range of user questions, no matter how trivial.

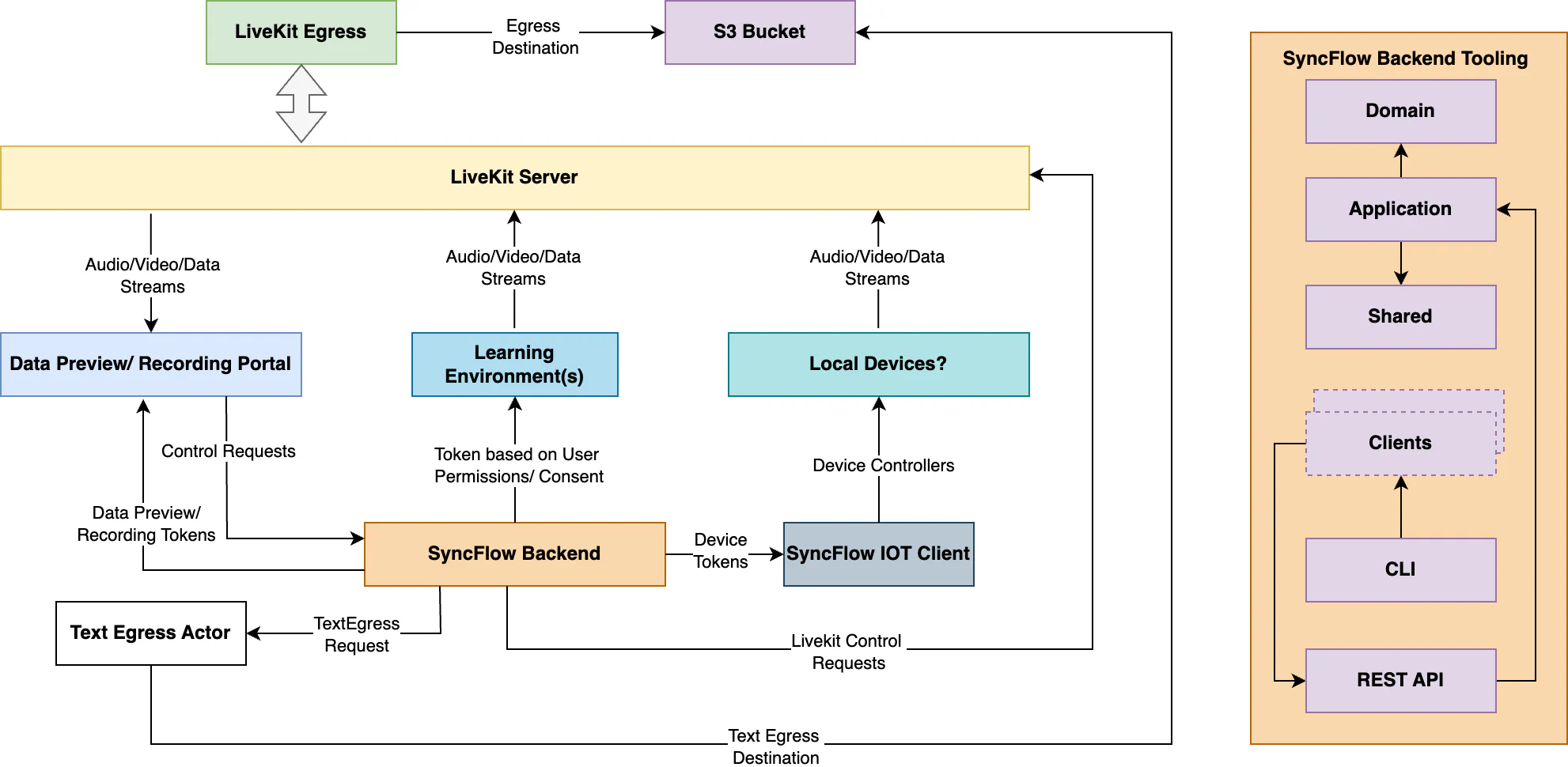

As we went further in the development of this NextJS app, Eduardo and I came to the conclusion that rather than building one-off solutions for the individual use cases, we need to come up with a generic solution that we could repurpose and enhance for all the studies within OELE and the Institute in general. This is when we brewed the idea for “SyncFlow: Harmonize Your Data Streams”. Our idea was to provide an orchestration dashboard that various learning environments could reuse to preview and record data for the classroom studies, provided they integrate with our ecosystem. The overall architecture would look like the following:

Proposed SyncFlow Architecture

Basically, we would create a backend for generating user tokens and managing room recordings, as well as comprehensive user management. A dashboard would be used to preview and record data, and an IoT client for streaming from local peripheral devices, as well as integration channels for various learning environments to join LiveKit rooms.

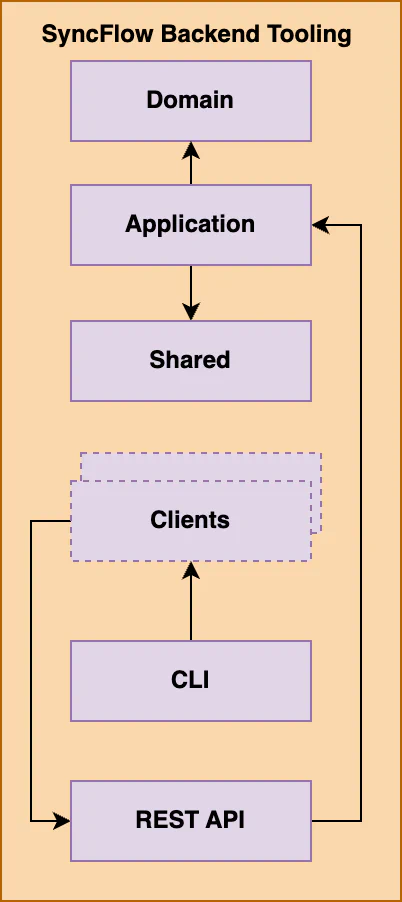

While trying to refactor the NextJS app to fit this pursuit, I quickly realized that we would require a more comprehensive solution than just a NextJS server-side solution. For example, I wanted to integrate IoT client support within the NextJS app, which was not the ideal use case for NextJS. So, eventually, we decided to plan the SyncFlow backend, following in the footsteps of the LiveKit ecosystem. We planned the following components for the backend:

SyncFlow Backend Components

The SyncFlow backend consists of the following components:

- Domain: The database and ORM interaction module for the system.

- Shared: Common reusable functions and utilities.

- Application: Main application logic for creating LiveKit rooms, sending recording requests, stopping recording, managing users, and handling API keys and secrets.

- REST API: The server and routes for the SyncFlow application.

- Client(s): REST clients, preferably packaged in various languages, for interacting with the REST API and the SyncFlow application.

- CLI: The command-line interface (CLI) for the SyncFlow application.

- IoT: The streamer for IoT devices.

With these components, we believed we could create a comprehensive integration of LiveKit for MMLA tasks. Eventually, the time came to choose a language for implementation, for which we opted for Rust. For the database, we selected PostgreSQL with Diesel as the ORM, and for the web server, we used Actix.

We successfully refactored the NextJS application to utilize the SyncFlow REST API, and all server-side actions of LiveKit were controlled by SyncFlow. For the entire deployment, there is a single LiveKit server that the admin users can use to create a LiveKit room. Additionally, a single S3 bucket is used to save and record data from the LiveKit Egress servers. We deployed the applications on a single AWS EC2 instance accessible at https://dashboard.syncflow.live. The application also implemented an API key and secret-based request middleware, where the application recognizes and authorizes requests with JWTs signed by the key and secret. Thus, the workflow is that admin users and developers of the learning environments generate their API keys and secrets and send requests to the SyncFlow API by signing a bearer token with their key and secret for SyncFlow. We also worked on a local data-sharing app https://example-app.syncflow.live for sharing local devices from the browser. However, we have not yet developed the IoT device streaming. We want to get this right and create a system with minimal friction, a task set for summer 2024. The mono-repo is available here, but still needs a lot of work and refactorings.

Our collaborators at NC State were keen on integrating ChimeraPy with the AI Institute’s flagship narrative-centered learning environment. While Vikram had already done some work with ChimeraPy, the integration we initially planned needed to shift to use SyncFlow. Therefore, we created an account for them, and they were able to implement and create an integration of “Crystal Island: EcoJourneys” with SyncFlow. This would stream audio, video, and game logs (Unity-based) to a room created in SyncFlow. During this collaboration, we also realized that in order to save application logs, we needed to write our own text/data saving plugin, as LiveKit egress only supports audio and video. So, we wrote a separate text egress plugin aptly named livekit-text-egress-actor.

The actual test of the SyncFlow integration was scheduled for the I-ACT study in April 2024, which took place at a middle school in midwestern United States. This provided a practical opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of the LiveKit implementation in a real-world educational setting.

I-ACT Study: Spring 2024

In March 2024, we were tasked with building and planning a data collection pipeline for an upcoming I-ACT study at a middle school in midwestern United States. The study would use “Crystal Island: EcoJourneys”, a 3D game that students would play to learn about aquatic ecosystems and pollution on an island in the Philippines. This integration presented significant challenges due to the following factors:

(a) Integration and collaboration were required across multiple teams at IU, NC State, and Vanderbilt.

(b) The system to be used was still under active development.

(c) There was uncertainty about whether everything could be delivered through cloud deployment.

Additionally, the original dates for the study were moved 15 days earlier than anticipated, making this task particularly challenging.

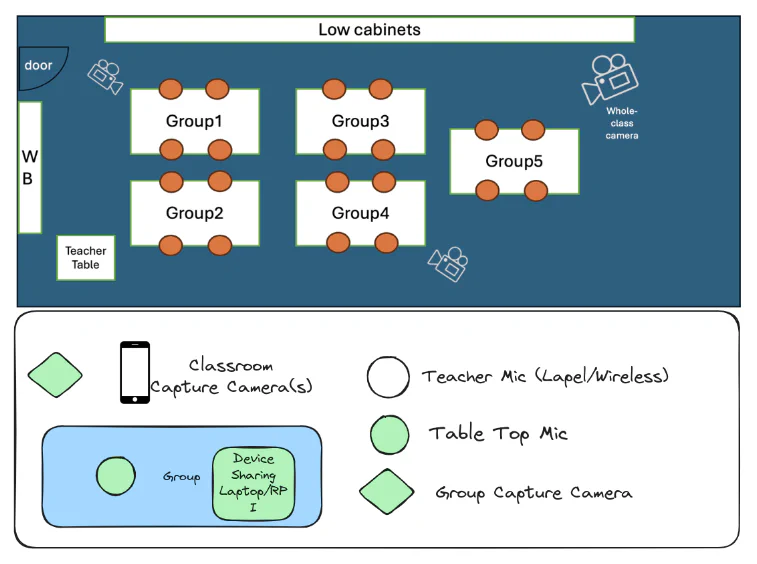

Based on the classroom layout provided by the IU team, students would play the game in teams of four, as the study focused on collaborative learning. The plan involved using tabletop microphones to capture group audio, cameras positioned to record classroom video from multiple angles, and individual audio and video recording for each student. The figure below illustrates this setup:

Classroom layout and data collection plan for I-ACT study, spring 2024

In addition to the audio and video modalities, we also intended to collect game play logs using the same setup. The idea was to collect synchronized audio, video and text streams through SyncFlow. Overall, this was a relatively complicated setup with multiple pieces, enumerated below:

- GAME (Unity + WebGL based): Game play with capabilities to send logs/audio/video streams

- Token Server For the game (Python): Permissions based token generation for streaming data for the game

- Data Preview Dashboard (NextJS): Data preview/recording dashboard

- SyncFlow Api (Rust): API for controlling/orchestrating everything

- SyncFlow data sharing app (NextJS): Camera/Microphone Sharing app

- LiveKit Server (Go): WebRTC SFU server

- Livekit Egress (Go): Data Recorder

- S3 Bucket (Minio/AWS S3): Data Recording Destination

- Text Egress Server (Rust): Data Recorder for textual data

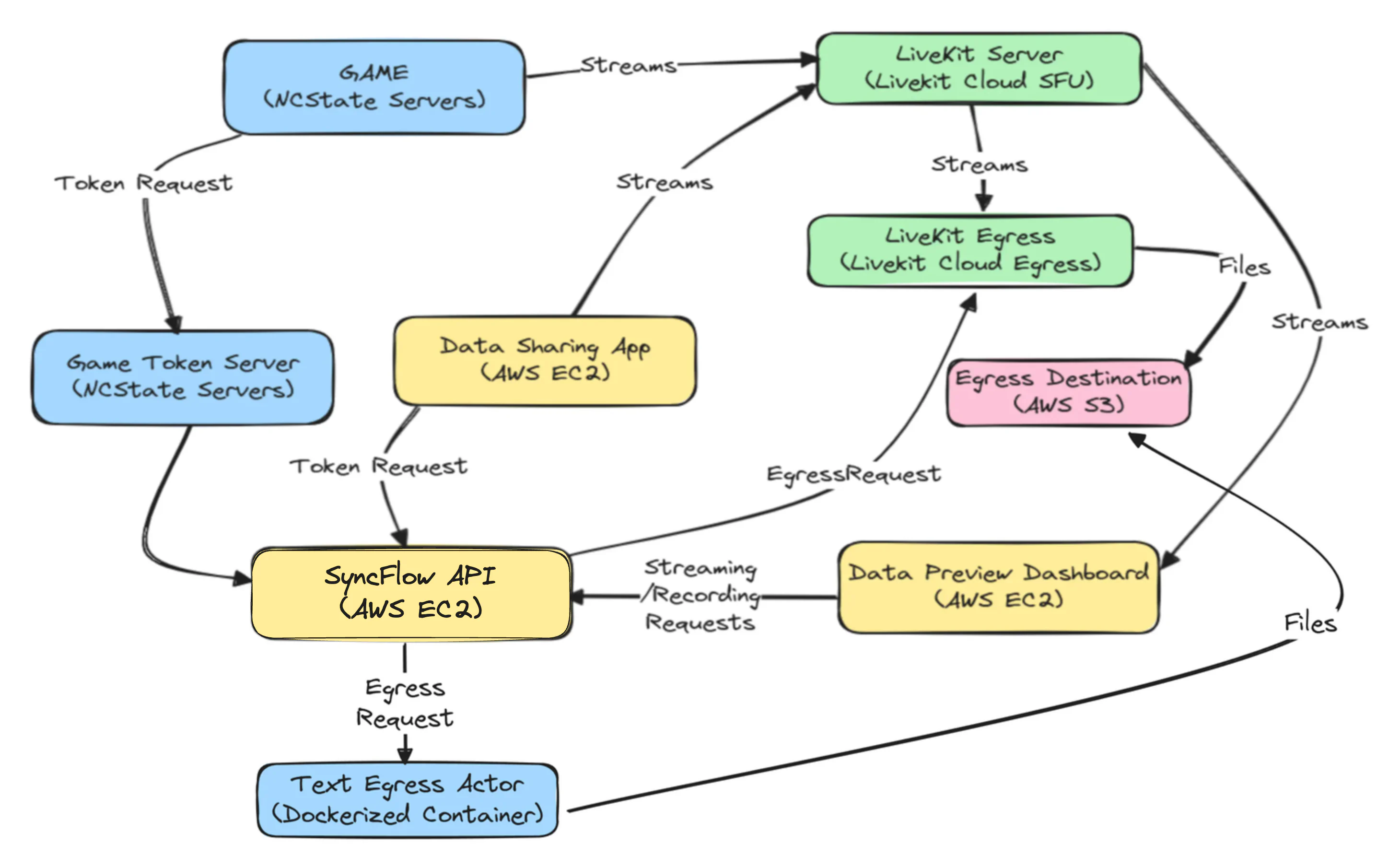

We not only needed to ensure that everything functioned cohesively but also had to thoroughly test this setup in advance. Testing proved challenging because replicating the classroom environment at OELE was required. At this stage, the integration between the game and SyncFlow was functioning well, but we hadn’t yet tested the system at scale. Initially, we were prepared for cloud based deployment of the systems, rendering the following deployment plan(figure below), most of which was achieved using GitHub actions.

SyncFlow-EcoJourneys cloud deployment plan for I-ACT study, Spring 2024

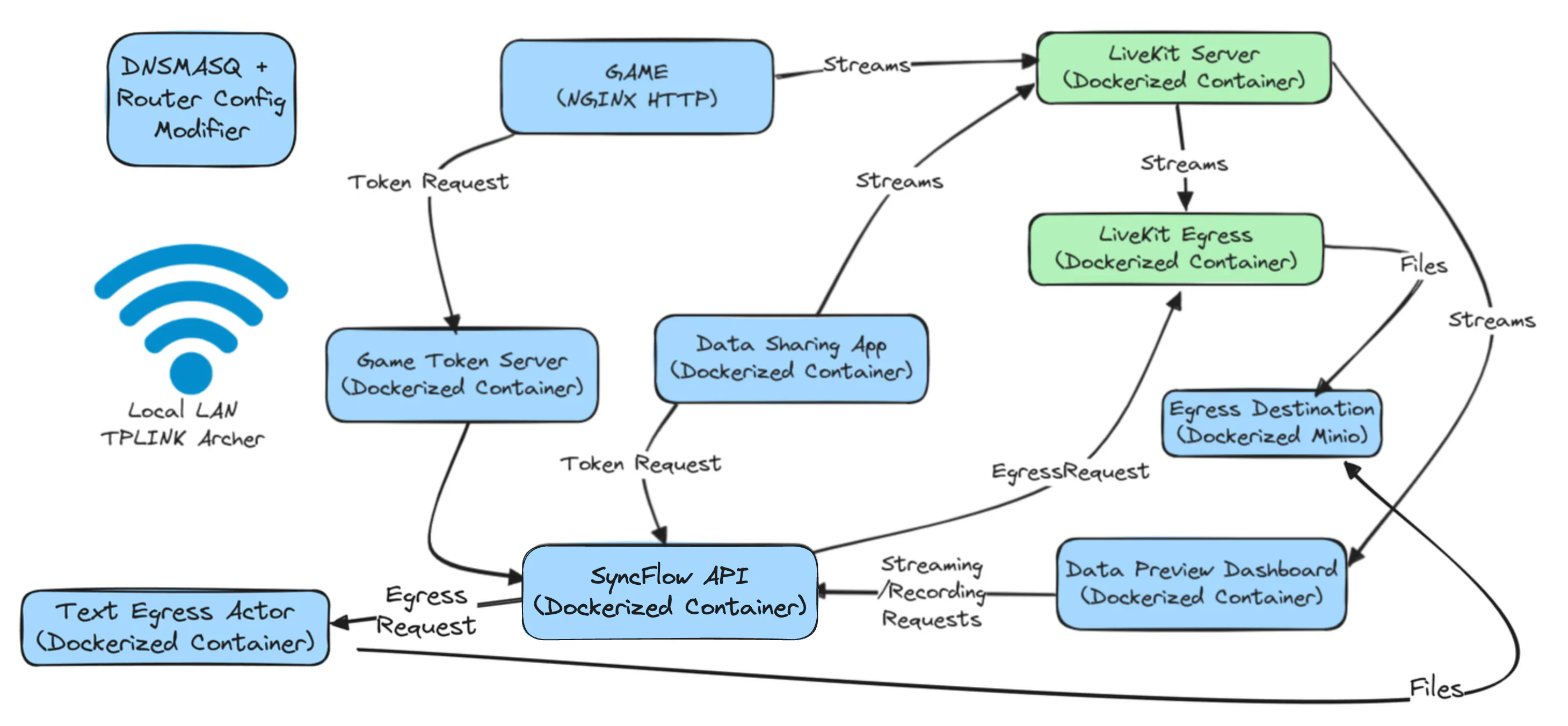

However, we were uncertain about the school’s bandwidth, which made it difficult to guarantee that everything could be delivered from the cloud. Given the tight deadlines, we opted for a local setup, which proved to be more challenging than expected. Firstly, we anticipated using each system in insecure contexts (HTTP) by bypassing browser security constraints, but this was not possible in the WebGL context. The process became cumbersome due to the unusual nature of the links, as we had to access various systems using the http://server-ip:port scheme. This added significant cognitive load for researchers and educators using the system. Additionally, security was a concern since LiveKit was also deployed in an insecure context.

To address this issue, we experimented with MkCert to generate fake security certificates and copied the server’s root CA to all client machines. However, we didn’t have access to the actual laptops that would be used in the study, as they were located in Indiana. Distributing the root CA across 20 machines would have been tedious regardless. To make matters worse, the LiveKit local deployment did not trust the self-signed certificates, rendering this solution ineffective for our requirements.

Finally, we realized that this local deployment plan needed to be more robust. Further research suggested that modifying the router configuration to point to a local DNS server to make fake domain names accessible over a LAN would be a feasible solution. However, trusted certificates were still required for HTTPS accessibility. At this point, we considered hosting our own LAN certification authority, but we didn’t have the time or resources.

Instead, we decided on a workaround. We already owned the domain syncflow.live and had generated certificates for it using Let’s Encrypt on an EC2 instance. To make this work, we generated Let’s Encrypt certificates for local domains (e.g., dashboard.local.syncflow.live, ecojourneys.local.syncflow.live) on an AWS EC2 instance, and copied these certificates to the local server. With this configuration and the duplicated certificates, the dockerized LAN deployment plan worked seamlessly.

The deployment files for the LiveKit-EcoJourneys LAN setup can be found in this GitHub repository, as shown in the figure below:

SyncFlow-EcoJourneys local deployment plan for I-ACT study, Spring 2024

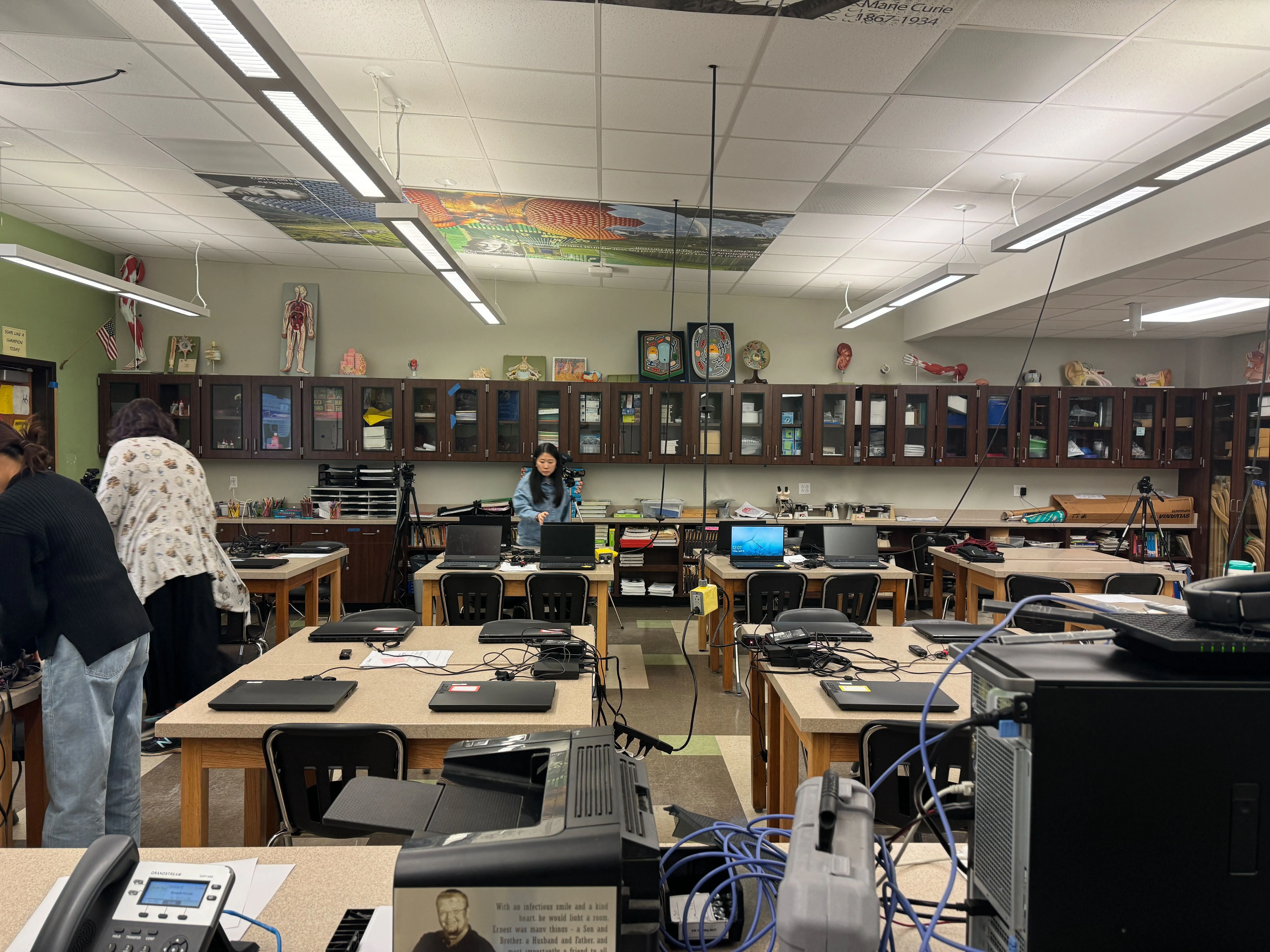

With this deployment plan, we were able to set up and test everything, and the preliminary results were promising. After wrapping up the tests at Vanderbilt, I packed my bags along with the server, microphones, router, and everything else needed, and drove to Bloomington, Indiana, in mid-April 2024. Upon visiting the classroom, we realized that the server and router could be stored there. On the first day of the study, we successfully collected 40-50 student audio, video, and text streams. However, we were short on microphones and decided to purchase a few tabletop microphones.

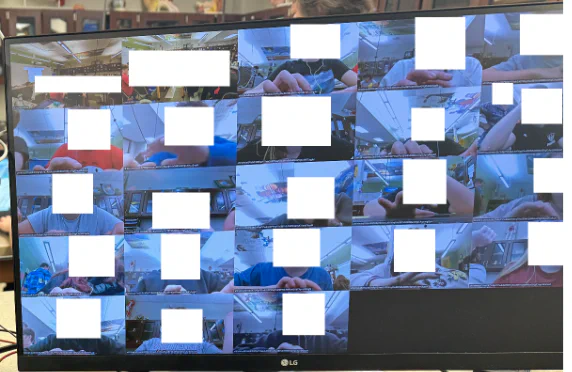

Classroom for I-ACT Study, April 2024

As the days progressed, we improved on prior results, streamlining the collection of group audio, classroom videos, and gameplay logs. Everything went smoothly, and over the five days of the study, we managed to collect nine gigabytes of data. The data was stored in the local minio deployment.

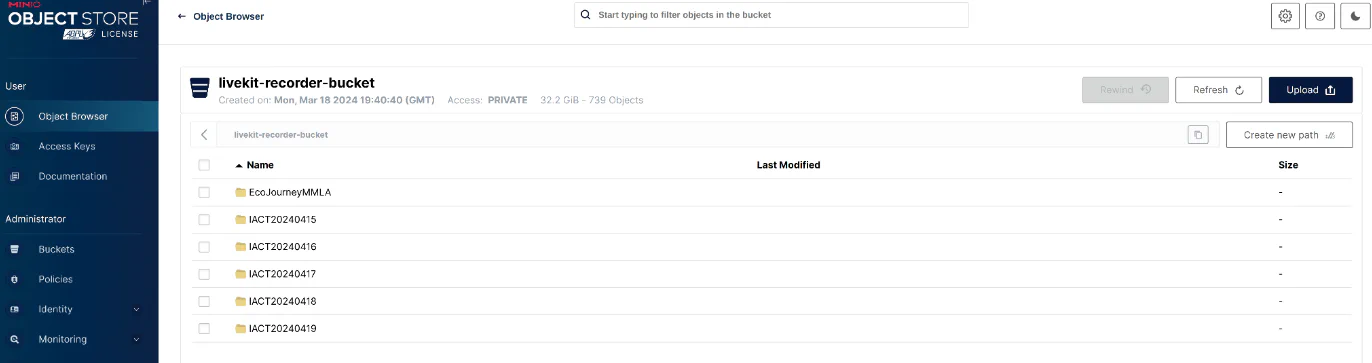

Preview of the data collected in the I-ACT study, April 2024

During one of the days, we tested the cloud setup since we had access to the school’s internet. To our surprise, the cloud-based deployment worked well for 10 participants. We then realized that a cloud-based setup would be ideal for future studies at the school.

Overall, the outcome of the study was positive, and we were able to collect the multimodal data as anticipated using SyncFlow, despite it being the first time the system was used. During the study, we made room creation configurable via Google Sheets, allowing room names to be date-specific. This proved useful since we had configured Egress to save streams by room name. Across the five days, we successfully achieved the following path structure in minio:

Path structure in minio for SyncFlow I-ACT study data collection

For each audio/video stream, depending on the codec used for streaming (LiveKit supports a variety of codes), we were able to save mp4/webm/ogg files, as depicted below:

Apart from the actual file, each file also saves a corresponding metadata.json, with the following keys:

"egress_id": "Unique ID for this egress operation"

"room_id": "Room ID for this egress operation",

"room_name": "Room name for which the egress was run on"

"started_at": "Seconds since unix epoch when this operation started"

"publisher_id": "Participant ID"

"track_id": "Track ID"

"track_kind": "AUDIO|VIDEO"

"track_source": "CAMERA|MIC|SCREEN_SHARE"With the metadata.json and started_at key, the offset calculations for each streams are trivial and we are able to achieve a single, unified timeline for the whole room experience. Apart from the audio and video logs, we followed the footsteps of the LiveKit Egress to save the textual data using similar S3 paths as well as metadata.

Practical Outcomes, Experiences and Lessons Learned

Regarding LiveKit integration, we initially used a manual egress mechanism where recordings only started with a button press and users had to select which track to record. However, this approach has limitations. For instance, in the I-ACT study, I had to manually select 40 participants and start text egress separately. Additionally, disruptions in the learning environment could cause participants to join and leave LiveKit rooms sporadically, leading to recording restarts and timeline gaps.

Overall, this research software tooling endeavor has been a rewarding learning experience for us. We finally had the opportunity to use Rust in one of our production systems, which I had always wanted to do. From debugging time alignments in ChimeraPy nodes to learning how to host an RTMP server, we’ve tackled a wide array of challenges. We have now incorporated four languages, a plethora of technologies, and various open-source projects into our ecosystem.

As with any field, the more you immerse yourself in it, the better you become. We’ve made many design decisions that needed eventual refactoring, but each challenge provided valuable lessons. For instance, in hindsight, relying on a single-language (Python + JS) solution for a project of this scale and diversity was unrealistic. We’ve also learned to prioritize developing applications that add value to the research projects within the institute rather than focusing exclusively on tooling. Despite any flaws in the software aspects, we can iterate if the minimum viable project is functioning.

Despite the challenges, our efforts have been fruitful. With different versions of the MMLA Pipeline software, we successfully collected data in real-world classroom settings. This data has contributed to numerous research projects and publications within OELE and improving integration among various partners in the EngageAI Institute.

The Road Ahead

The road ahead is promising. At the institutional level, numerous multimodal analytics research projects are ongoing and nearly production-ready. At this point, different aspects of the MMLA Pipeline not only support data collection but also facilitate analysis and feedback. We’ve conducted several integration studies with the learning environments used within the institution, mainly focused on data collection. Through these studies, we’ve identified numerous opportunities for enhanced analysis and feedback integration. We plan to incorporate institutional research to refine this feedback for multiple learning environments.

At the same time, we aim to implement several software engineering improvements. While the dashboard UI performs well for 20-30 simultaneous streams, it requires paginated views and proper planning to handle hundreds of streams. The current architecture supports only a single LiveKit server configuration and one S3 storage location. Over the summer, we plan to adjust the backend so that users conducting multimodal data collection for MMLA can utilize their own LiveKit deployments and storage, further streamlining the process. This would position SyncFlow as primarily an orchestrator with access to user and project resources. Additionally, to address the recording issues, implementing an Auto Egress mechanism would automatically start and stop recording as participants enter or leave rooms, which we intend to refactor.

Additionally, we intend to invest significant software engineering efforts in the LiveKit IoT client to better support data collection from various sensors and local devices, thereby meeting our needs comprehensively.

Call To Action

We invite researchers, educators and developers interested in MMLA to collaborate with us on the MMLA Pipeline. Join us to shape a comprehensive, scalable solution that advances educational research.

By contributing to our open-source project, you can help refine real-time data collection, analysis, and feedback methods that empower learning environments. Together, we can address integration and feedback challenges while improving educational outcomes.

If you have any questions/suggestions, please reachout at umesh.timalsina@vanderbilt.edu or eduardo.davalos@vanderbilt.edu.

Special Mention: Eduardo

A special note of graditude to Eduardo for his invaluable contributions to this endeavor and for the countless brainstorming sessions we’ve shared. Your creativity and dedication have significantly shaped this project.

Thanks NSF

A sincere thank you to the NSF Engage AI Institute for supporting a multimodal learning analytics strand and designating OELE as its leader. Your investment has empowered us to build a unified software architecture that streamlines tasks while delivering crucial feedback to improve educational research and enrich learning experiences.